Jean Pocock’s Memories

As a young woman, Jean Pocock, Yorke Lowe’s daughter, worked for the Great Western Railway during World War II, when their staff were evacuated to Aldermaston. Some 50 years later she recorded her wartime memories.

John Lowe ran a shop on the corner of Silchester Road and Broadhalfpenny Lane in what until recently was ‘The Broomsquire Hotel’. Kelly’s Directory first lists John as a grocer in 1907, so the name Lowe as a grocer and draper was well established in Tadley by 1925 when John’s son Yorke moved the family business from Lowe’s Corner to Mulfords Hill (where Sainsbury’s is today) following his father’s retirement.

A very clear photograph of the front of Lowe’s Store (previously Blakes Store) Mulfords Hill, probably during the 1930s.

When America entered the war in December 1941, I was 21, single and living at home with my parents. Prior to the commencement of war Tadley was a quiet country hamlet, the men worked in the fields and copses, or the besom industry for which the village was quite well known. Others worked at the Central Ammunition Depot (CAD) at Bramley, or in the nearest towns, Basingstoke or Reading. The main roads through the village had grass verges and ditches, no street lighting, and the majority of the side roads and lanes had gravel surfaces. Between Tadley and the village of Aldermaston were the woods and fields that originally belonged to the Aldermaston Court estate, and it was this land which was used for the aerodrome. Huts for the men employed in the building of it were erected in the fields on the Tadley side, and this project gave work to some of the local men, and some women who were employed in the canteens, and in cleaning the living accommodation.

The RAF first occupied the aerodrome but there was very little activity until 1942, when the Yanks arrived.

The peace of our village had been shattered by the Irish labourers, the RAF, and now the Americans. They were an odd looking crowd in their working gear, and the fact that the living accommodation, administration and mess rooms were spread out in the fields between the existing houses, meant quite a lot of coming and going. The GIs just ambled along, and even when in file couldn’t march as the RAF had done. This highly amused the children, who could often be seen mimicking them. The GIs were very nervous and when the air raid warning was sounded would jump into the nearest ditch and became quite alarmed because the children, who by now were used to the siren sounding and nothing happening, continued playing. Each evening when the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ sounded over the tannoy, the GIs would stand still and salute, the little children would do likewise.

We found the different dialects quite amusing, but it was not long before we could correctly guess which quarter of America they came from, and it was very interesting to hear about their life back home.

The first batch to arrive, came into the shop (which at that time was the only one inside the camp area), asking, ‘What can we buy’. My mother would explain that certain goods which were in short supply had, naturally, to be kept for our customers. Cocoa, which at that time was fairly plentiful, was very popular with them. They would hold out a handful of money saying ‘Take what you want’, and mother would then try to teach them the English coinage. They collected silver 3d bits to make charms for bracelets, and were eager to purchase brass objects to send home. They were very homesick and I remember being asked by one of them, if I would just write to his sister Violet as if I had known her all my life, mentioning his Christian name, and she would then know that he was in England. Whether the letter reached her I do not know – he was shortly moved.

Informal photograph of two American servicemen (Siera and Boyce) on guard duty in an ‘upground’ type air-raid shelter. (7 February 1944).

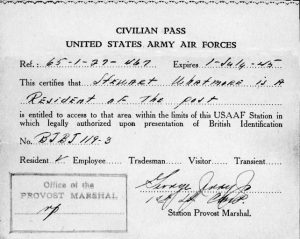

The next batch to arrive were smarter and better equipped, and of course, the camp area was improved and enlarged. Film shows, dances, concerts etc were arranged for their off-duty hours. As the camp grew, security got tighter and sentry posts were erected at the extremities of the camp. This meant that quite a proportion of the northern area of the village was within the camp area. All residents were issued with passes, and people coming to our shop from outside of the camp were given a chit by the sentry; this had to be stamped by us, and handed back on their return through the gate. This security seemed to slacken off at times and then tighten again, and sometimes when an extra special restriction was on, a guard would accompany the people to the shop.

At one time we purchased our milk from a farmer who was a customer of ours, but lived outside the camp on the opposite side of the camp, and our milk was often delivered by jeep. I travelled right through the camp daily to my work near Aldermaston station.

I recall an occasion, later in the war, when relatives from Birkenhead were coming to stay with us for a short holiday, it just happened to coincide with one of these extra restricted times, and although we were allowed to come in and out of the camp, my relatives were not allowed in, and we had to find accommodation outside for them for a couple of days until the restrictions eased.

The publican of The Cricketers, Heath End with American airmen Sergeant Callaghan (left) and Sergeant Mathies.

The Americans were soon accepted by the ‘village’, the camp had given us a new outlook. The GIs were really friendly towards the children, and were generous with candy and gum. The girls were never short of boy friends; a number of the women did washing for the GIs, and apart from monetary payment, received gifts of precious nylons, soap and packets of washing powder. Even when the latter commodities were rationed, a number of customers did not bother to take their ration as they were well supplied by the GIs.

In the middle of 1943 the 1227 Military Police Company (Aviation) arrived at the camp, and one of the sergeants came into our shop and asked if he might look around. He was keenly interested in the various goods displayed, and told my mother that his name was Richard A Brown, and that his parents and family ran a store in Bridgeport, New York State. We were just as interested to learn how they ran their business and what goods they sold. My mother invited him to bring a couple of pals in for the evening, and we learnt that they worked together in the cookhouse. These three (Richard, Thomas Wilkins and Goodie) spent a great deal of their off duty hours at my home. They would read, write letters home and Richard sometimes helped with filling up the fixtures in the shop and weighing up goods. They would bring chocolate, candy, cashew nuts etc, perhaps a tin of meat or fruit. They really enjoyed a ‘trifle’ pudding. Sometimes we would all go to the pictures in the nearest town. We were not interested in dancing, but the company did arrange dances with the Wrens from the Women’s Royal Naval Service depot at Burghfield.

I recall my father and I took the three ‘boys’ up to London to show them a few of the landmarks. Through our acquaintance with an MP we were able to see part of the Houses of Parliament, and this really interested them. We also had a meal in one of the Lyons Corner houses, where we went round the ‘Salad Bowl’. And the fact that one could help oneself to as much as one wanted, was a great delight.

Not only did the airfield comprise the area now occupied by AWE, it extended south covering large parts of Tadley. Locals living inside the airfield boundary had to have a pass to enter or leave.

They spent most of Christmas 1943 with us, joining in the games and sing songs round the piano, as and when their duties allowed. They liked meeting our friends and being treated like one of the family.

After they moved to Andover in 1944, several trucks would come up twice a week bringing GIs back to Aldermaston and Burghfield to visit friends. They went to France a few weeks after D-Day, and Richard occasionally used to write for the three of them, then eventually the letters ceased.

Different batches of troops came to the camp and I think it was early in 1944 that gliders arrived on the aerodrome; the usual practice runs increased and security tightened. We used to attend the base chapel and often the troops would be there in full kit in readiness. It was getting near to D-Day. By this time I was working in the office at the Naval Ordnance Inspection Department at Burghfield and had to go outside the camp to catch the bus as the bus route had been altered when the guard posts were erected.

An informal photograph of four American servicemen taken outside one of the buildings on Aldermaston airfield; (left to right) Bill Langstaff, Tom Towers, Ed Sullivan and Andrew Henderson.

On returning home about 5.00 pm one day, we were not allowed through the gate and we knew that something very hush-hush was going on. After waiting about two and a half hours we were allowed in, and that night waves of planes and gliders took off, and some returned. There was a strange feeling in the base chapel the next Sunday night, some of the men were in full kit and as the service progressed they left, and we realised that their turn had come.

Another GI who became one of our regular visitors was Sergeant Bill Councill of the 72nd Troop Carrier Squadron, US Army. He, with Virgil Bellenger, who worked in the padre’s office, and some of their friends who attended the chapel, used to come home for supper on Sundays. We would chat and have sing-songs round the piano. One vivid memory was Christmas Eve 1944, previously there had been a fall of snow which had frozen on the trees making icicles, it was very pretty. When they left after supper, we gave them an invitation to come in after lunch on Christmas Day. They thanked us, and one said ‘You’ll be hearing from us before then’. We thought nothing more of their remark, but at mid-night we were awakened by the sound of music coming over the tannoy, it was ‘Christians Awake’ and this was followed by ‘Silent Night’ sung as a solo by Virgil. The air was crisp and hoar frost glistened in the moonlight. This scene always comes to my mind when I hear these carols.

Early in January 1945, my parents sold the business and we moved to live in Reading. Shortly after we moved, Bill rang up to ask if I would play the organ for the chapel services the next day, as the regular player was sick and the deputy on duty elsewhere. A jeep arrived early on Sunday morning to transport me and a girl friend to the camp. It wasn’t a very comfortable ride but we were tickled pink with the VIP treatment we received, especially in the officer’s mess during the day.

Eventually I lost touch with the camp, but Bill has corresponded each Christmas since and often mentions some of the boys, including Virgil and Captain Webster, the Padre. Bill is now living at 215 Watkins Drive, Hampton, Virginia.

As, at every camp, there were the occasional fights between the men, a few drunks would cause a bit of trouble. Romances caused a few heartaches, some girls married their GIs, a few became un-married mothers. On the whole, I think, they were reasonably well-behaved; or maybe, we were lucky.

Ernest ‘Ernie’ Kimber’s Memories

Ernie Kimber was born in Tadley in 1900. Before his retirement he was a civil servant at the Central Ammunition Depot, Bramley. In 1935, the Kelly’s Directory lists Ernie as an insurance agent. He made many contributions to Tadley: as clerk to the local Parish Councils, as governor of Tadley School and as a long time member of Tadley Silver Band and co-founder of Tadley Concert Brass. He was author of a book written in 1983, ‘Tadley During My Time and Before’, which recounts his memories of the parish and its people. Ernie died in 1988.

The American DC3s or Dakota transport planes became a familar sight over the Tadley area as for many weeks they circled overhead towing gliders and there was much speculation as to what it ‘was all about. However, the answer came before dawn on the 6th of June 1944 when the whole neighbourhood was awakened by the roar of planes ‘warming up’ on the airfield and we knew that something big was underway. It was of course D Day and none of us who witnessed it will ever forget the sight of masses of Dakotas with their gliders in tow heading south. The gliders were of course filled with troops as part of the invasion force and they were to be dropped off on the French coast. Many Tadley families had made friends with the GIs, many of whom sadly were never to return.